- Home

- Gita Varadarajan

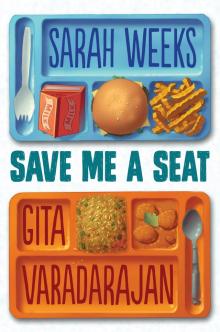

Save Me a Seat

Save Me a Seat Read online

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Monday: Chicken Fingers

Chapter One: Ravi

Chapter Two: Joe

Chapter Three: Ravi

Chapter Four: Joe

Chapter Five: Ravi

Chapter Six: Joe

Chapter Seven: Ravi

Chapter Eight: Joe

Tuesday: Hamburgers

Chapter Nine: Ravi

Chapter Ten: Joe

Chapter Eleven: Ravi

Chapter Twelve: Joe

Chapter Thirteen: Ravi

Chapter Fourteen: Joe

Chapter Fifteen: Ravi

Chapter Sixteen: Joe

Wednesday: Chili

Chapter Seventeen: Ravi

Chapter Eighteen: Joe

Chapter Nineteen: Ravi

Chapter Twenty: Joe

Chapter Twenty-One: Ravi

Chapter Twenty-Two: Joe

Chapter Twenty-Three: Ravi

Chapter Twenty-Four: Joe

Chapter Twenty-Five: Ravi

Thursday: Macaroni And Cheese

Chapter Twenty-Six: Joe

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Ravi

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Joe

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Ravi

Friday: Pizza

Chapter Thirty: Joe

Chapter Thirty-One: Ravi

Chapter Thirty-Two: Joe

Chapter Thirty-Three: Ravi

Chapter Thirty-Four: Joe

Chapter Thirty-Five: Ravi

Chapter Thirty-Six: Joe

Chapter Thirty-Seven: Ravi

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Joe

Chapter Thirty-Nine: Ravi

Chapter Forty: Joe

Chapter Forty-One: Ravi

Chapter Forty-Two: Joe

Chapter Forty-Three: Ravi

Chapter Forty-Four: Joe

Chapter Forty-Five: Ravi

Chapter Forty-Six: Joe

Chapter Forty-Seven: Ravi

Chapter Forty-Eight: Joe

Chapter Forty-Nine: Ravi

Ravi’s Glossary

Joe’s Glossary

Fran Weeks’s Recipe for Apple Crisp

Raji Suryanarayanan’s Recipe for Naan Khatais

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Copyright

Most people in America cannot pronounce my name.

On the first day at my new school, my teacher, Mrs. Beam, is brave enough to try.

“Sur-yan-yay-nay,” she says, her eyebrows twitching as she attempts to sound it out.

“Sur-ee-ah-neh-RI-ya-nan,” I say slowly.

She tries again, but it is no better.

“I’m going to have to work on that,” she says with a laugh.

I laugh too.

Suryanarayanan is my surname. My first name is Ravi. It’s pronounced rah-VEE, with a soft rah and a strong VEE. In Sanskrit, it means “the sun.” In America, people call me RAH-vee, with the stress on the first syllable. That doesn’t mean anything.

“Patience is a virtue,” Amma reminds me often.

She believes that, with time, people will learn how to say our names correctly. My grandmother tells her not to hold her breath.

We moved to Hamilton, New Jersey, a few months ago—May 13 to be exact. I am fresh off the boat, as they say. My father got a promotion at his IT company in Bangalore, so they transferred him to America. In India, Amma, Appa, and I had our own house with a cook and a big garden. We even had a driver to take us wherever we needed to go. My grandparents lived in their own flat nearby. Now we all live together in a town house, in a place called Hamilton Mews.

Things are very different here in America. Appa takes the train to work. We don’t have a cook anymore, so Amma has to prepare all the meals herself. Our new house is much smaller than the old one. There is only one bathroom upstairs, which I share with my grandparents. I wouldn’t mind so much except that Perippa likes to take long showers and Perimma leaves her teeth in a glass by the sink at night.

I learned to speak English when I was very young. We speak mostly English at home and I went to an English-medium school, but for some reason, people here in New Jersey have trouble understanding me when I speak. I am trying to learn how to swirl my tongue to sound more American.

My grandmother doesn’t like it. “Be proud of who you are and remember where you come from,” she tells me. “If you’re not careful, you’ll turn into one of them. Your grandfather didn’t slave in the tea plantations so that his only grandson would become some rude, overweight, beef-eating cowboy.”

I don’t think Perimma likes America.

My school in India was called Vidya Mandir, which means “temple of knowledge.” My new school is called Albert Einstein Elementary. Perimma could hardly wait to show off to all her friends at home that her grandson had been accepted to a school named after a scientific genius.

I’m not a scientific genius, but I am a very good student. My favorite subjects are math, English, and sports—especially cricket.

“Boys and girls, please welcome our new student, RAH-vee,” Mrs. Beam says after she has taken the roll call. “He’s come to us all the way from India! Isn’t that exciting?”

Mrs. Beam is short and round. When she smiles, her eyebrows touch each other.

As I look around the room, a sea of mostly white faces stares back at me. I feel a little nervous. It is my first day of fifth grade in room 506, and I am the only Indian in my class. There is one other, a boy named Dillon Samreen, but he doesn’t count. He is an ABCD. American-Born Confused Desi. Desi is the Hindi word for Indian. I can tell Dillon is an ABCD, because he speaks and dresses more like an American than an Indian.

“Tell us something about yourself, RAH-vee,” Mrs. Beam says, smiling at me.

“Yes, ma’am,” I say, standing at attention.

Everyone laughs.

Mrs. Beam claps her hands. “Boys and girls, where are your manners?” she asks. “Go on, RAH-vee. We’re listening.”

I push up my glasses and continue. “My name is Ravi Suryanarayanan, and I just shifted from Bangalore.”

Everyone laughs again. What’s so funny? I wonder.

Mrs. Beam claps her hands. Her eyebrows are twitching like mad. “Boys and girls, is this how we welcome a new student to Albert Einstein?”

The room gets quiet. The spotlight is on me. I can feel the whole class staring. This is my first day of school in America, and things are not going well.

Mrs. Beam turns to me. “You can call me Mrs. Beam,” she says softly. “And, RAH-vee? Here in America, students don’t need to stand up when the teacher calls on them. Do you understand?”

Of course I do. I push up my glasses and rub my nose. It’s something I do when I’m nervous.

Mrs. Beam comes over to my desk. She has a look of pity on her face.

“Don’t worry, RAH-vee,” she says, patting me on the shoulder. “You can introduce yourself to the class later, after you’ve had a little time to work on your English. We have a very nice teacher named Miss Frost in the resource room. I’m sure she can help you.”

I want to say:

My English is fine.

I don’t need Miss Frost.

I was top of my class at Vidya Mandir.

But here is what I do instead:

Push up my glasses.

Rub my nose.

Sit down and fold my hands.

My friends and teachers at Vidya Mandir would have a good laugh if they could see me now—their star student taken for an idiot. What a joke!

Mrs. Beam is writing out our homework on the board. I open my notebook and carefully copy down the assignment. Out of the corner of my eye, I see Dillon Samreen starin

g at me. He looks like a movie star straight out of Bollywood. His long, shiny black hair falls over one eye; with a quick jerk of his head, he shakes it away. Then he smiles and winks at me. I smile back. Dillon Samreen may be an ABCD, but I think he wants to be my friend.

My name is Joe, but that’s not what most people call me. Not at Einstein anyway. I’ve never been a big fan of school—except for lunch. Eating is the one thing I’m really good at. I’ve always been tall for my age, but lately I’ve been growing so fast my clothes don’t fit anymore, even the ones we bought a few weeks ago. I’m always hungry.

A lot of kids wouldn’t be caught dead eating school lunch. They call it mystery meat and slop, but I don’t mind. Every week it shows up in the same order: chicken fingers, hamburgers, chili, macaroni and cheese, pizza. By the way, it’s not a coincidence that Tuesday is burger day and Wednesday is chili day, because at Einstein, hamburgers get recycled. It’s not as bad as it sounds. The leftover burgers from Tuesday get dumped into a big pot with beans and some other junk and, presto chango, on Wednesday you’ve got chili.

Everybody knows I don’t talk much at school. My best friends, Evan and Ethan, used to call me Blabbermouth as a joke, but I guess I’m not going to be hearing that much now, since they both moved away over the summer. To be honest, they were a little weird, but I’m going to miss them anyway.

Evan, Ethan, and I ate lunch together every day last year, and they had to go to the resource room for extra help, same as me. (Not that we had the same problems—for one thing, they were both super hyper and I’m not.) This year, I’ll have to go by myself to see Miss Frost, and I’m not sure who I’m going to eat lunch with. Probably no one.

People think you’re unfriendly if you don’t talk to them. But they don’t understand that it’s a problem for me that it’s so noisy in the cafeteria.

My brain and noise don’t get along.

Last year, I had Mr. Barnes for my teacher. Mr. Barnes is epic. He can bounce a Hacky Sack off his knee a hundred times without messing up. I had never even heard of a Hacky Sack until Mr. Barnes brought his to school. It was pink, which Dillon Samreen thought was hilarious. He said something mean about it behind Mr. Barnes’s back, and all the girls laughed. Sometimes I wonder what’s wrong with girls, but then I remember I already know what’s wrong with girls—everything.

Mr. Barnes is African American. He shaves his head and wears bow ties—real ones you have to tie yourself. He must have talked to Miss Frost about me, because he never asked me to read out loud in front of the class or come up to the board to do math problems. He understood those things are hard for kids like me.

Some people don’t mind having everybody looking at them—Dillon Samreen, for instance. He wears his pants pulled down low, with his underwear sticking out the top. He wants people to see it. His boxers have dollar signs on them, or dice, or lobsters, and he has special ones for holidays too, with candy corn or Christmas trees or red hearts for Valentine’s Day. Dillon is famous for his boxers, but his real claim to fame is his tongue, which is long and pointy like a devil’s. When he sticks it out, it makes the girls scream. He thinks he’s the smartest kid at Einstein, and he might be right. He’s definitely the meanest. Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to be Dillon Samreen, but that is something I’ll never know.

Mr. Barnes was the first teacher I ever had who liked me. Miss Frost likes me, but she likes everybody, so it doesn’t count. On my final report card, Mr. Barnes wrote that I was “a valuable member of the community.” My mom was so proud she stuck it on the refrigerator with a magnet. It’s still there.

* * *

TODAY IS THE first day of school, and Mr. Barnes is the first person I run into when I get here. He’s wearing a red bow tie with little blue whales on it. I’m pretty sure it’s new, or at least I’ve never seen it before. Last year, Mr. Barnes had seventeen different bow ties that he always wore in the same order—starting with the green one with white diamonds and ending with the orange-and-purple-striped one. Mr. Barnes’s bow ties were another one of my favorite sequences.

“Yo, Joe,” he says. “How’s it feel to be a fifth grader?”

“Good,” I tell him. “At least so far.”

Maybe this year will be different, I think. Maybe Dillon Samreen won’t be in my class.

But when I get to room 506, there he is, standing over by the windows with his underwear hanging out. Polka dots.

Lucy Mulligan and a bunch of her annoying girl friends are standing around him, chanting, “Do it, do it, do it!” They want him to stick out his tongue, but Dillon won’t.

“Come on, Samreen, let’s give ’em what they want!” Tom Dinkins shouts before sticking out his own tongue and wagging it at the girls.

Tom Dinkins is a Dillon Samreen wannabe. The girls don’t care about his tongue.

“I warn you,” Dillon tells his fan club, “I think it grew a little over the summer.”

Lucy and her friends start jumping up and down, screaming, “Eeeew!”

One thing I will say about Dillon Samreen: He really knows how to play a crowd.

All the screaming starts to get to me, so I do the in-two-three, out-two-three breathing Miss Frost taught me. If that doesn’t work, I’ll have to use my earplugs. I always keep a pair in my pocket just in case. They come in different colors, but I like the tan ones best, because they don’t show as much. They’re made out of some kind of squishy foam rubber, and when I wear them, I can still hear people talking, only it’s softer, like when you’re underwater or have a pillow over your head. I’m allowed to wear my earplugs in school whenever I want, but mostly I use them in the cafeteria, on the playground, and in gym class.

“Settle down and take your seats,” announces Mrs. Beam, my new teacher. This is her first year teaching at Einstein, and she looks a lot younger than any of the other teachers I’ve had. She’s shaped kind of funny—wider on the bottom than the top—and she’s shorter than me, which is weird, considering that she’s my teacher. She seems nervous, and there’s something freaky about her eyebrows.

At Einstein, kids have to sit in alphabetical order. Every year since kindergarten, my seat has been right behind Dillon’s. I know the back of his head by heart. Mrs. Beam has made name cards for us and put them on the desks, but when I go to take my seat behind Dillon, somebody’s already sitting in it. He’s a shrimpy-looking kid with thick glasses and greased-down black hair parted on the side. I’ve never seen him before, and I’m not sure where he’s from. His skin is darker than mine, but not as dark as Dillon’s or Caleb Burell’s. When I look at the card sitting on his desk, I see his name is about a mile long and full of y’s and a’s.

He seems kind of nervous too. He keeps rubbing his nose and looking down at his hands, which are folded in his lap like he’s in church or something. His shirt is so white it hurts my eyes to look at it, and he’s got it tucked in and buttoned up all the way to the top. When Mrs. Beam asks him to tell the class about himself, he stands up like he’s in the army and calls her ma’am—which is about the only word he says that you can actually understand. Everybody starts laughing, and for a minute, I think, Hey, maybe fifth grade isn’t going to be so bad after all.

Maybe Dillon Samreen will decide to pick on this new kid with the weird name and the funny accent instead of me.

Mrs. Beam tells us we are going to play some games called icebreakers. I can already tell that school in America is going to be easy for me. At Vidya Mandir, we never played games during class. On my first day of fourth grade, my teacher, Mrs. Arun, gave us a test! The first game Mrs. Beam teaches us is called Fruit Salad. I am on the team called Bananas, and Dillon is on the Apples. Another game is called Wink Murder. In this game, one person is the “murderer,” and he or she has to knock people out by winking at them. I find this game a bit confusing because even when Dillon is not the one chosen to be the murderer, he still winks at me. The last game we play is called Venn Friends. For this game, Mrs. Beam assigns us partne

rs. I hope that she will put me with Dillon Samreen, but instead my partner is a pale, skinny girl called Emily Mooney.

“You’ll have a few minutes to interview each other,” Mrs. Beam explains. “Find out as much as you can about your partner. For instance, what kind of music does he or she like? What is his or her favorite food or sport? When you’ve finished your interviews, you’ll create a Venn diagram showing all the things you have in common.”

“What the heck?” says a red-haired boy with freckles.

He doesn’t know what a Venn diagram is, so Mrs. Beam has to explain it. At Vidya Mandir, we learned how to make Venn diagrams in third grade.

“Each of you must draw a circle and fill it with a list of things that your partner enjoys,” Mrs. Beam says. “Then you and your partner will draw two overlapping circles. Where the circles intersect, you’ll make a list of all the things you’ve discovered you have in common.”

At first, I think this will be an easy game for me, but every time I try to ask Emily Mooney a question, she giggles and says, “What?” Then, when I try to answer her questions, she does the same thing. Appa says that someday I will be interested in girls, but that day has definitely not come yet. When Mrs. Beam calls time, the only thing Emily Mooney and I have found to place in the intersection of our diagram is that we are both in room 506—and that was my idea. I am glad when Mrs. Beam tells us it’s time to get ready for lunch.

At Vidya Mandir, our lunch period began at one o’clock. Fifth graders at Albert Einstein Elementary School eat lunch at 11:30 in the morning. When I get to the lunchroom, the first thing I do is look for Dillon Samreen. In India, my best friend, Pramod, and I always ate lunch together. Afterwards, we’d play cricket in the field behind the school.

I spot Dillon standing in the queue waiting to buy his lunch. They are serving something I have never heard of before called chicken fingers. Most of the tables are filling up quickly, but I spot an empty table on the opposite side of the lunchroom and sit down. While I wait for Dillon to join me, I carefully lay out the cloth napkin that my mother packed for me, neatly folded with a spoon tucked into it. I’m not feeling very hungry, but Amma will be upset if I don’t eat the lunch she made me.

Save Me a Seat

Save Me a Seat